On Photography Education

Is There an Age to Express the Inner Being?

A few months ago I read with great interest a series of articles on photography education published in Source Magazine (#72) and written by a variety of lecturers, course leaders and students from different universities in Ireland and the UK. Its closing article, “Teaching Photography as a Dead Language”, by Greg Lucas and Jane Fletcher, summarizes the practical issues currently faced in photography education as discussed by its previous contributors and proposes different solutions to solve the undergoing crisis.

Among the many problems arising throughout these articles, there was one that especially caught my attention – probably because I have experienced the situation both as an MA student and a Lecturer in Photography. The issue in question dealt with the fact that during the past two decades students have been asked to express themselves through photography – that is, pointing “directly” at themselves – rather than looking at the world through their camera lens. It was argued that studying the subject had turned into an egocentric introspection into the students’ self, and that group critiques at university had started to consist of some sort of a collective psychotherapy session, where the tutor took the role of the psychologist and the group supported the patient, offering different readings of their personal and intimate situations. So, instead of commenting on the technical qualities of their projects, the students presenting their work would be analysed by the group and advised as to how to deal with their psychological issues – whatever they might be.

I must admit that, when I read these words, I could perfectly visualize myself in those group crits, and as I tried to remember the debates we used to have during my postgraduate studies, certain comments – rather funny now – came back to mind: “Perhaps you should go deeper into that relationship with your father after he got divorced”; “I suggest that you explore your memories of the time your sister was killed in that car-crash – there might be some interesting imagery there waiting for you”; “Listen, if you need to talk to someone, let your work speak by itself, you will certainly feel more relieved after this process”.

According to Greg Lucas and Jane Fletcher, by the time students start learning photography at a Higher Education level, since most of them are still rather young, there is no way they will have gone through enough life experiences to allow them to produce a meaningful project. Their suggestion, therefore, is that photography should be taught like a “dead language” – such as Greek or Latin – where the subject is studied mainly through a series of investigations and experiments – leaving behind the idea of using photography as a “creative expression” – and focusing instead on understanding the history, visual culture and concrete technicalities of the media, in an attempt to abandon the course-content that concerns the “artist statement”. In other words, the subject should be taught as a practical media course rather than a fine art course.

It’s interesting that this conclusion was written in the context of a photography publication such as Source Magazine, which focuses on promoting fine art and pure, cutting-edge conceptual photography. The argument behind their thesis, however, lies in the fact that when a student enrols in a BA Photography course – funded often by their parents or guardians – the great majority of them do it with the hope of finding a job in the photographic industry – that is, working as commercial photographers – whereas the lecturers who teach them have indeed run away from that industry and decided to teach the subject in order to continue producing, albeit for lower remuneration, their fine art work.

Well, I must admit that as a teacher, I do believe in the importance of offering students the appropriate tools to understand the media in its technical depth and historical context – or as Greg Lucas and Jane Fletcher suggest, teaching it as a dead language. But, short of the extremes of turning a photography course into some sort of psychotherapy procedure, there’s certainly a great deal of learning students can gain when attempting to express themselves. It makes them grow intellectually. It allows them to understand their inner being and put it in relation with their external circumstances. It helps them develop as individuals regardless of their age, and when they do produce – and, trust me, they sometimes do – incredibly meaningful projects, it finally makes them experience the unbearable pain of lucidity.

And it is precisely in this pain where photography educators succeed.

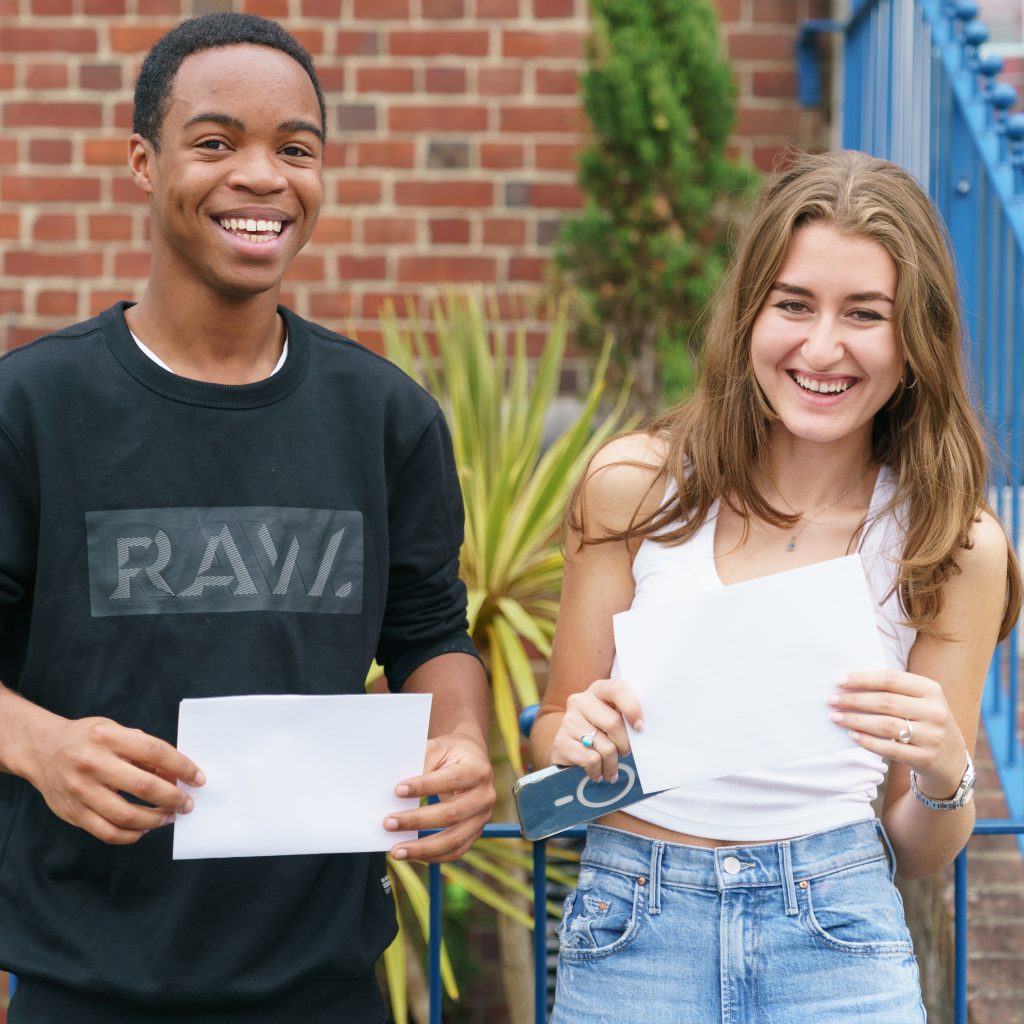

To end this note, I’d like to share with you this work by Helen Findley, one of my A-level photography students at Brampton College. The author of these photographs is now 16 years old.

All Untitled, from the series To where she would pretend, 2013 © Helen Findlay