The Story of the Brain in 10½ Cells’ is a book written by Richard Wingate, published in 2023. Wingate is a Professor of Developmental Neurobiology at King’s College London. He studies the development and evolution of the brain as well as exploring the interfaces between science, arts, philosophy, history and social sciences. I discovered this book while exploring the ‘Staff Recommendation” section at the gift shop at the Wellcome Exhibition. It caught my eye because I want to study neuroscience at a microscopic level after A levels, so I thought, it’s a book about brain cells, why not? However this book not only inspired me on a scientific level, but also creatively, which I hadn’t expected. It was the thing that kept me hooked throughout the book. The way that he amalgamates art and science so seamlessly was intriguing to say the least.

One of my favourite things I learnt in the book was when Wingate explores certain debates in neuroscience, specifically when the concept of brain cells first came around, of which there were a surprising amount. He describes the conflict between Ramon y Cajal and Camillo Golgi, ironically the first people to win a shared Nobel prize. Golgi believed that brain cells were not individuals and that they acted as ‘one continuous’ ‘seamlessly joined’ network of fibres. This completely disregarded Cajal’s universal law of dynamic polarisation, the idea that information flows along dendrites, as well as acknowledging the existence of the synapse between neurons. I found this to be interesting because it really puts into context just how far neuroscience has come in a very short amount of time. The function of dendrites and existence of synapses is something widely understood, even at a GCSE level, so it is remarkable that these concepts were so heavily debated at the time. And when you think about the technology they had available at the time as well, it puts into perspective just how difficult research was back then, especially about something like brain cells.

The writing itself makes neuroscience feel more like an art form. While scientific jargon is still used, it is interwoven into the artistic way in which he writes, using a whole plethora of similes, metaphors and analogies. You don’t feel like you’re reading non-fiction , it’s more like reading an Oscar Wilde novel, for example in the way he describes neurons when he sees them for the first time. He describes them as “[…]beautiful. They are compelling and varied in the same way that trees have a sinuous and emotional beauty. […] Its shape is nothing less than the physical manifestation of a fragment of thought”.

Wingate compares the shape of neurons to trees on multiple occasions throughout the book, which I really like as it emphasises that while some people just look at them as something ‘sciency’, they are part of nature that evolves and grows in the same way a tree would. It also makes the whole concept of neurons more quantifiable and easy to imagine. Due to their miniscule size, one cannot always comprehend just how impressive the role they carry out really is, until you link it back to something more familiar, such as trees, which are easier to visualise. For example, if you think of the amount of neurons in your head, 100 billion, that doesn’t sound as much as 100 billion trees which would take up more than 10 times 802,440,000,000㎡ .

His passion for neuroscience also comes through in his writing, particularly when he describes the emotions he feels when observing brain cells. For example when he describes how he was often times “frozen in awe” or when he “[…] jumped up and punched the air or paced the room trying to contain [himself]”. I find that his passion is quite contagious, and it’s difficult to not start to feel just as excited as he was at the time, and you want to jump up and down with him!

Another personal highlight of this book was the way Wingate explores the intersection of neuroscience and the arts, which is particularly of interest to me as I’m doing both biology and art at A level. He explains how for many years, scientists would have to draw their findings as they didn’t have the means of taking photos. He describes the process as “A necessary way of expressing knowledge and understanding”. Personally, I think there is a lot of irony in this quote because in the present day, arts and sciences are seen as almost polar opposites. You are either good at one or the other, but never both.

This is in contrast to how it was during the times of Cajal and Golgi, where it was almost necessary to be skilled in the arts to make it in science, because “To draw is to know” according to Wingate. For example, when researching brain cells, neuroscientists would have to adjust the magnification of their microscopes with one hand, while simultaneously drawing their observations with the other. However, though it is most likely more diluted now, I do find that whenever I connect with scientists on, for example, social media, the creative arts are also a passion for many of them. So even now, the remnants of the old ways, though discrete, are still there, just hidden I suppose, as they are not essential in laboratories like they used to.

What I do find interesting is that I find this more common in disciplines in biology such as neuroscience, perhaps because anatomy must come more naturally to visual thinkers. I find that personally, when I’m studying brain anatomy it becomes a lot easier to me than when I’m studying cell processes for example. I think Wingate captures these ideas perfectly. He describes neurons, and the process of the eventual discovery, as if neuroscience was in fact an art, and in doing so, really captures the beauty of it all. As Wingate says, “There is art at the heart of this science”.

In conclusion, whether you’re someone doing a science A level and looking for something to add to your personal statement, or whether you’re just interested in neuroscience and want to learn more about brain cells, I highly recommend this comprehensible as well as interesting read!

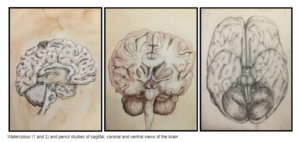

Watercolour (1 and 2) and pencil studies of sagittal, coronal and ventral views of the brain…

By Anabelle Bowman, student